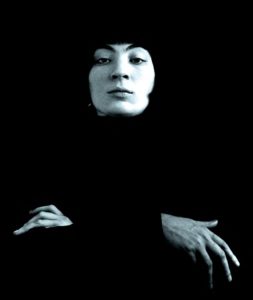

ELISO VIRSALADZE: “For me Oleg is not over yet”

Interview is dedicated to 70th anniversary of Oleg Kagan

Olga Yusova

Sviatoslav Richter called Oleg Kagan a “top-grade violinist”, Sergiu Celibidache described him as “embodiment of harmony” while Yuri Bashmet called him “superman.” Gennady Rozhdestvensky spoke of extraordinary “radiance” emanating from his heart while Mstislav Rostropovich emphasized kindness as his main quality. Oleg Kagan died on 15 July 1990, at the age of 43. Though short, his life was an exceptional, full life of outstanding musician and person. He left a lasting imprint on those who were close to him as well as those who only saw him on stage. Charm, amiability, affection, warmth, refinement – all these important human qualities added to his enormous talent and contributed to the formation of a unique personality harmoniously combining everything that was necessary for life and stage.

Sviatoslav Richter called Oleg Kagan a “top-grade violinist”, Sergiu Celibidache described him as “embodiment of harmony” while Yuri Bashmet called him “superman.” Gennady Rozhdestvensky spoke of extraordinary “radiance” emanating from his heart while Mstislav Rostropovich emphasized kindness as his main quality. Oleg Kagan died on 15 July 1990, at the age of 43. Though short, his life was an exceptional, full life of outstanding musician and person. He left a lasting imprint on those who were close to him as well as those who only saw him on stage. Charm, amiability, affection, warmth, refinement – all these important human qualities added to his enormous talent and contributed to the formation of a unique personality harmoniously combining everything that was necessary for life and stage.

Oleg Kagan would have turned 70 this year. He achieved much – was the best student of David Oistrakh, won largest international competitions, performed all masterpieces of violin and chamber music repertoire and dozens of works by modern composers. However, his creative life was not smooth as peculiarities of the time he lived in significantly affected his biography.

The film director Andrei Khrzhanovsky made a movie about him – “Oleg Kagan. Life after life.” In his diaries Sviatoslav Richter wrote a lot about Kagan. Today, Eliso Virsaladze is going to speak about her stage partner and close friend – Oleg Kagan. Her recollections of that great person and outstanding musician as well as of the epoch which has already been left far behind are important for us, contemporary people, as they enable us to take an impartial look at pros and cons of that epoch.

Ms Virsaladze, your recollections of Oleg Kagan will be a continuation of your story about Richter as there was a very close human and creative link between these two musicians. Moreover, Richter’s diaries remain one of main sources of information about Oleg Kagan. For example, after Kagan performed Bach’s compositions for violin at one of Richter’s house concerts, Richter wrote down in his diary: “Natasha and I are listening [to Kagan’s performance] and trying to criticize (if anything to criticize….). We see the view of Moscow and golden domes of the Kremlin through loggia windows. Spring is gradually setting it…” When reading this you have a feeling as if you witness the whole situation – Oleg Kagan playing Bach while Richter looking into the distance at the Moscow Kremlin… You also attended such house “assemblies” at Richter’s apartment. They are now seen as a phenomenon – not mere gatherings of quite a close circle of people, but great art events of those times, a sort of cultural “sectarianism.” How did that phenomenon emerge? Did it have causes and peculiarities characteristic for that time? Were those house concerts and gatherings a sort of alternative to monumentality, grandiosity of official art, of that epochal mindset and worldview establishing itself on great stages?

I myself rarely played at Richter’s house concerts. Surely, I never turned down an invitation from him to such a concert, but those invitations were not frequent. In contrast, Natasha Gutman and Oleg Kagan spent much time with Richter and their relationship was way more intensive. Richter was a man of action; there was always something happening around him, something interesting and new which he invented and tried to involve other people into it. To what extent he succeeded in that, I cannot tell. He always entertained some illusions that he could connect people, create common interest for those who were admitted to his house and his circle. In fact, that circle was not very limited, sometimes the public was quite mixed there.

One may call the December Evenings festival as a true alternative to the official art of those times. That was indeed a unique phenomenon, so much impregnated with Richter’s individuality that with Richter gone, it continues virtually unchanged since its inception. I think, the same holds true for Rudolf Barshai’s orchestra which for many years after his death has remained the same as it was under him. There is something incomprehensible, almost mystical for me in both cases, as if the spirit of their creators continues to live in them and lead everything there.

Recollecting unofficial cultural life in Moscow of those times, which took place at private gatherings and in kitchens, art critic Paola Volkova wrote: “That was a milieu with idols, leaders of the time, of the generation… And never ever they discussed money or property, but only key things…” Do you remember your talks with Natalia Gutman and Oleg Kagan at Richter’s place? What were the topics you were concerned about? What developments in the field of art did you discuss?

We were concerned about everything and discussed the topics which other contemporaries used to discuss. I find it difficult to single out any particular subject now, but I remember we talked about books, movies of those times. Often these were works of art which did not gain massive popularity. If they were European films, we watched them in small movie theaters and naturally, discussed them thereafter, sharing with our impressions. What kind of books did we discuss? Often they were banned books, samizdat editions. Everyone is aware of that – I am not saying something which you may not know. Now we can talk about that without fear. But let me stress that everything we learned at those times was special, extraordinary for us, arousing intense emotions among us. I do not experience similar shocking feelings now. Today, perceptions of things have changed. In those years people with shared interests represented a community with similar attitudes towards many developments. I remember, Richter’s fans, after listening to his performance, were leaving the concert hall in a state of euphoria and they all seemed very much alike though each of them was an interesting personality in this or that way. It is precisely this sort of unity, shared feelings and interests that aroused among visitors of Richter’s apartment. One should have a perfect understanding of peculiarities of those times. A main topic of that life was the migration of artists from the country. Some people

emigrated while others stayed and both these categories of people were much discussed – why did one leave? Why did another stay? This is what that epoch looked like. I remember, the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra with its conductor Yuri Temirkanov was going on a concert tour to the United States and seeing them off, [the then minister of culture] Yekaterina Furtseva, when shaking hands in farewell, told each of them: “Have a good trip! And please, come back, come back!” Lots of things happened in those times. It was a whirlwind of various emotions. At the same time, it was the period when culture, arts, theater flourished incredibly. Richter had avid interest towards all this; he was always aware of everything happening on the stages of Moscow. The same holds true for Oleg Kagan. They both were extremely interested in everything. Kagan was always amazed at Richter knowing everything, remembering everything. They passionately discussed all new developments in the field of art. They never talked about money! But it was something that was possible only in those times. However, I am sure, were they alive, they would have remained the same. Everything changes but they would not have changed. The situation is different today. Art has become easily accessible and people no longer feel any euphoria from new works of art. Everyone seems to have

become sophisticated and to understand everything… When reading something or listening to someone I often wonder how is that they know everything and are so confident in discussing any topic… Neither Richter nor Kagan had such confidence. They never asserted anything, never imposed their opinions on others. In that they were alike and it is not accidental that they became such close friends spiritually. Their attitude towards issues of performance was similar too. Neither of them would ever insist that something must be played only in this way, not otherwise. There always were possibilities for different interpretation, nothing was untouchable. However, each final performance of a composition was in such a perfect form that it seemed the composition could not have been performed better. However, next time, they would find a new interpretation for the same composition.

In Khrzhanovsky’s movie Rostropovich recalls that Oleg Kagan suffered much from restrictions imposed on him – he was not allowed to travel abroad, to perform as many concerts as he would want. However, he was not a dissident or nonconformist. According to his friends, Kagan was an amicable person with soft character. How come things turned out as described by Rostropovich in the movie?

It was Natasha Gutman who was banned from travelling abroad. She was not allowed to travel abroad for eight years. I remember, all were happy when, at the end of the day, she went abroad for a tour. Goskoncert [the entity responsible for organizing cultural events] was busy promoting other musicians and organizing their concerts. Goskoncert would never promote Oleg Kagan; this would never happen! For our part, we were not able to do this ourselves back then. Moreover, we were not focused on a career advancement – the word “career” was derogatory for us. Natasha’s complaints that Oleg Kagan was not invited as often as he deserved caused negative reaction among many managers in the West. She was reproached for caring too much about her husband. However, she cared about him not as her husband but as an artist because she knew what a great artist Oleg Kagan was. To understand all this one should be well aware of the situation of those times and how things were arranged here and in the West. Could western managers realize what a great artist Oleg Kagan was? No, of course, not. That’s life – there has always been musicians who perform undeservedly many concerts and vice versa, undeservedly few concerts.

It was Natasha Gutman who was banned from travelling abroad. She was not allowed to travel abroad for eight years. I remember, all were happy when, at the end of the day, she went abroad for a tour. Goskoncert [the entity responsible for organizing cultural events] was busy promoting other musicians and organizing their concerts. Goskoncert would never promote Oleg Kagan; this would never happen! For our part, we were not able to do this ourselves back then. Moreover, we were not focused on a career advancement – the word “career” was derogatory for us. Natasha’s complaints that Oleg Kagan was not invited as often as he deserved caused negative reaction among many managers in the West. She was reproached for caring too much about her husband. However, she cared about him not as her husband but as an artist because she knew what a great artist Oleg Kagan was. To understand all this one should be well aware of the situation of those times and how things were arranged here and in the West. Could western managers realize what a great artist Oleg Kagan was? No, of course, not. That’s life – there has always been musicians who perform undeservedly many concerts and vice versa, undeservedly few concerts.

However, Oleg Kagan was not entirely banned from travelling abroad. He performed a lot of duets with Richter, including in the West. This, sometimes, gave rise to insulting rumors which were spread because of jealousy. Malicious gossips had it that Kagan owed his career to Richter. Some pretended not to understand why Richter chose Kagan among all violinists while, in their opinion, there were more renowned ones…. That was extremely unfair. We all know perfectly well how Richter appreciated Kagan for his outstanding qualities of the musician. But such unpleasant talks about him started now and then. Kagan tried not to pay attention to them, but anyway, they hurt him very much.

The film about Oleg Kagan depicts a context which creates an inevitable impression that he was subject to pressure. It contains a fragment from an interview he gave in German not long before his death, in which he says: “At that time we came to realize that our freedom is inside ourselves. You might be deprived of a possibility to travel around the world but staying home with a book of Dostoyevsky, you may be thousand times freer.” On the one hand he confirmed a fact of restriction, but on the other hand, he seemed to underline that he did not pay much attention to that.

In the context of the film everything might look a bit different. The filmmaker had to give a certain line of course to a film. It is difficult for me to talk now about all those things without emotions because I have a feeling as if I am returning to the past and start recollecting those unpleasant characteristics of that time. It hurt Oleg Kagan, of course. Saying that it did not hurt him would mean saying nothing. He was full of energy at that time and could travel around the world performing concerts but he lacked this opportunity. But what hurt him more was seeing Natasha and his friends being concerned about him as they believed that he lacked something. In reality he possessed much more than anyone else – he had something which others lacked. He possessed something more important and valuable that filled and enriched his life – something he talked about in his last interview.

The film about Oleg Kagan is a good work, of course, but I do not like it. By the way, I do not like the film about Richter either, which was made by [Bruno] Monsaingeon. This is just my personal trait. It is good that the film was made and it exists as a document about Kagan and that renowned personalities from the field of art of various countries say such nice things about him in it. I am very fond of Khrzhanovsky who spared no efforts to create this film and I understand how difficult it was to make it shortly after Kagan’s death. I remember how Natasha [Gutman] suffered after his death and she wanted this film to keep details about him. But, I do not like that Oleg is shown in the film as he looked not long before his death. We, healthy people, do not think whether it is correct to show a person in such a condition. I put myself into Oleg’s shoes: should I like to be filmed when I am completely helpless, cannot control myself and say something which I would not have said were I healthy? My answer is negative to that question. Thus, this is a matter of personal taste.

Like other musicians from Richter’s circle, Oleg Kagan played pieces of modern composers. When reading Richter’s diary I paid attention to one episode in which he wrote about a vinyl record of Berg chamber concerto for violin, piano and wind instruments, performed by Oleg Kagan, which was removed from sale since it was not in demand. This episode conflicts with other episodes in the diary, in which Richter wrote about numerous concerts where compositions by Schoenberg, Berg, Hindemith alongside compositions by our composers – Schnittke, Gubaidulina were performed in Moscow. In one of her interviews Natasha Gutman even underlined that it was precisely the 20th century music that resonated among listeners in those years. One may wonder what triggered such a great interest towards those composers among both society and musicians. The compositions that attracted crowds of people back then are virtually no longer performed today; let’s look at, for example, Oleg Kagan’s repertoire: Offertorium and other compositions by Gubaidulina, sonatas and Concerto Grosso by Schnittke and many other compositions created in those times. Was that a form of social protest? A burning interest towards anything new? A longing for free forms of self-expression, overstepping the boundaries of tradition which was associated with official narrative? How can you explain the fact that there is no such interest for it today? Is there nothing that may trigger protest among musicians today? Why the authorities were occasionally against the performance of musical compositions created in those times?

Well, your question contains an answer! Because everything was always banned in our country and in art many things were done to counter those bans. For example, Moscow intelligentsia was crazy about the banned film Repentance and until Perestroika, everyone watched it on video cassettes. It was that ban that made the film very popular, because I do not consider it a masterpiece. It required huge efforts to get consent on the performance of Schnittke’s compositions. Some people might have interpreted his music as a protest – call it as you like. Back then, it merely stirred up interest; cultural events were very important in the lives of people as people had nothing else. In those times, information used to spread fast among people of art, everyone understood and knew everything.

I know; there is a record of Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso №2 performed by Oleg Kagan and Natalia Gutman in 1958, which took place in an overcrowded Grand Hall of Moscow Conservatory. The compositions, you have listed above, are performed today too. But they do not cause the sort of excitement they did when they were introduced to public. Actually, it is difficult to perform modern music in such a way as to stir up desire among public to listen to it. Do you know what an effort it took for Richter and Kagan to perform Berg’s chamber concerto for violin, piano and 13 wind instruments? How many rehearsals they had and how hard they worked to make it perfect?

Many compositions are created here now, but very few are performed. It seems impossible to learn about new musical compositions because there is no professional criticism. If you work in the field you may learn about something. But how can audience learn about it? After the collapse of the Soviet Union, musical criticism disappeared altogether and instead, they started reveling in writing nasty things about great musicians. In the West, composers are promoted and performed. Though for some reason, such composers as [Paul] Hindemith or [Karol] Szymanowski are performed more often here than in Europe.

As regards Oleg Kagan, it was not difficult for him to find a suitable mode of performing modern music. He

felt and understood modern music as perfectly as he felt and understood romantic music or Viennese classics.

He could always do everything easily and naturally. He was an open, very light person able to find a

right approach to any person, even a villain, and that person would inevitably succumb to his charm and lose

his/her disgusting qualities for some time. It was amazing how easily Oleg could do that.

Yuri Nikolaevsky once said about Oleg Kagan: “He considered ethical side important in everything. He always showed it and in performing he pursued ethical objectives alongside esthetic ones. His interpretations were the interpretations of a decent, good person.” Does performance allow to judge about personal qualities of a musician?

I liked Nikolaevsky very much and I understand perfectly well what he meant. Undoubtedly, by his nature Oleg Kagan was a man of good morals. However, analyzing his performance from this standpoint is extremely difficult. Music is diverse and in order to perform it, a musician must be able to be diverse too. And Oleg was diverse, flexible, light in that. But to answer your question, key in a composition is not the qualities of a performer but the qualities of a composer. And it is well known to everyone that geniuses did not often comply with acceptable moral norms.

In other words, you consider a combination of genius and villainy possible although you had examples of Richter and Kagan.

Of course, I do. For me genius is the highest artistry, ability to transform. Throughout my life I have met quite a number of talented people whose actions were far from perfect.

Did you admire the art of such people?

Only until the moment I came to encounter their human qualities. When values that are important for me are trampled, I stop admiring those people who trample upon them. All this is interconnected for me and I am consistent in this matter. If I do not like a performer’s personality, I do not like him/her as a musician either.

What qualities are important for you in a musical partner? Everyone who performed with Oleg Kagan speak about his outstanding qualities of a partner. How is an intuitive interconnection of musiciansmanifested in a duet? Is it necessary when performing chamber music to experience equal intensity of emotions such as equal depth of sorrow, equal happiness, equal sensation, something like that?

It is very difficult to identify at what moment of performance the understanding emerges. Sometimes there is a need to agree upon something before the performance. But this is not the main thing, nor is agreeing central. The performance itself is like a talk – when we conduct an ordinary talk each of its participants has its own “stance.” We listen to one other and are often quick to understand someone who is close to us; sometimes we may not even finish a sentence or phrase because we know our interlocutor will understand it. The same holds true for an orchestra. Each musician has his/her own attitude to what he/she “says” through music. Understanding between me and Oleg Kagan did not require much discussion or absolute clarification. It emerged as a mutual process, as exchange of feelings, conversation between people quickly understanding each other. Music is a special type of art and it does not need maximal, sheer clarity; we do not talk, we perform and when we perform there emerges a different sort of understanding – a musical understanding, not the understanding that emerges in interaction through words.

It is very difficult to identify at what moment of performance the understanding emerges. Sometimes there is a need to agree upon something before the performance. But this is not the main thing, nor is agreeing central. The performance itself is like a talk – when we conduct an ordinary talk each of its participants has its own “stance.” We listen to one other and are often quick to understand someone who is close to us; sometimes we may not even finish a sentence or phrase because we know our interlocutor will understand it. The same holds true for an orchestra. Each musician has his/her own attitude to what he/she “says” through music. Understanding between me and Oleg Kagan did not require much discussion or absolute clarification. It emerged as a mutual process, as exchange of feelings, conversation between people quickly understanding each other. Music is a special type of art and it does not need maximal, sheer clarity; we do not talk, we perform and when we perform there emerges a different sort of understanding – a musical understanding, not the understanding that emerges in interaction through words.

Of course, there should be similarity in emotions. Or to put it more accurately, there should be a similar understanding of and attitude towards music. When playing a sonata by Beethoven, your and your partner’s hearing of it should be identical. Next time, however, the hearing of the same composition may be absolutely different, but still identical in both partners. Moreover, you must be fond of the partner – one must not perform with someone whom he/she dislikes. One should have cordial feelings towards a partner – this makes the understanding easy in an ensemble. I remember when Oleg Kagan came to congratulate me after listening to my performance for the first time – I was playing Beethoven’s concerto №4 in the Great Hall of Conservatory – I was very pleased because of the feeling of closeness and understanding that emerged. What I mean is that he understood perfectly well with all his subtlety what I was doing.

I did not know a more ideal partner than Oleg. Unfortunately, we performed together very little! We did not perform even a single sonata by Mozart, such a pity! I would love to play Mozart with him! We performed sonatas of Schumann, Beethoven, Franck, Schubert’s Fantasie – these are all duets. But we performed not only duets – we played Mendelssohn trio, Brahms quarter and quintet. Mozart quartet… But duets were very few. Moreover, let me confess: I am not able to perform with any other violinist seriously, truly… Of course, I have partners and I perform with them but there is no one I would really want to play with as much as I wanted to play with Oleg; especially, when I have my single eternal partner – Natasha Gutman.

Oleg was such an outstanding partner that I played sonata of Franck only with him. This happened only once, at a private concert in Greece and since then I have not been able to play that sonata with anyone else. The same holds true for Schubert’s Fantasie – I performed it with Oleg Kagan only once; I will never forget it and will not be able to perform it again with anyone else. I have a record of festival in Telavi where we performed Schubert’s Fantasie; the quality of record is not high but it is still very valuable for me because listening to it I recall all this.

However, the record of Tchaikovsky Trio in A minor performed by Richter, Gutman and Kagan at a December Evenings concert is an absolute masterpiece. There are compositions which are played often and well, but for me those special performances become the best, which are close and valuable for reasons which are very difficult to articulate. The abovementioned performance of Trio is exactly like that.

From numerous recollections about Oleg Kagan, for example, recollections by Schnittke, one may conclude that he was a very modest person, never showed himself off, preferring to stay in a shadow; he did not like to be a leader. How did this fit with the necessity to carry out the duties of primarius in ensembles?

He used to transform when playing in an ensemble and if by his part he had to perform the role of a leader he did it perfectly well – i.e. he was able become an absolutely natural leader.

When you think about Oleg Kagan which of renowned violinists of the past time evokes associations with him or comes to your mind to draw parallel with Kagan? [Yehudi] Menuhin, perhaps?

Perhaps, yes. I agree. Also with Kreisler as Oleg Kagan had similar charm and lightness. Qualities of his teacher, Oistrakh, were also apparent in him. However, I would rather say that he was versatile. Or to be more accurate, he was absolutely unique, different from anyone. I was amazed at one of his qualities which is strange to musicians – he could admire his colleagues. It is astonishing how people in the field of music dislike one another, how they seek some absurd reasons to belittle their colleagues. But Oleg was an absolutely different person. He was never mean, never! This speaks about the greatness of his personality. When a person is so talented he/she never pays attention to trifles.

Once, having listened to records of Mozart’s concertos №3 and №5 performed by Oleg Kagan and conducted by David Oistrakh, Richter said: “I think Oleg is close to correct understanding of Mozart.” Then he underlined that the record was a proof of superiority of the Russian school of violin. What did Richter mean in “correct understanding of Mozart”? Was it about stylistics of performing Mozart as understood at that time? Are Oleg Kagan’s records in demand today? Do they continue to serve as an example of understanding Mozart?

Assumedly, what Richter meant was that Oleg seemed to be born to play any composition in a natural, light, effortless way. That gave rise to a feeling of naturalness of his “Mozartianism.” He never invented anything; he never had a single false gesture or intonation deliberately designed to attract or cheat listeners. He was extremely honest; that’s why Richter valued him so much. Mozart is like a litmus test: his compositions make human falseness reveal instantly. Kagan had a perfect sense of time, he always fit into the style ideally. This was, first of all, intensive inner feeling towards this or that composer.

Most important for Richter were the honesty of Oleg and his phenomenal qualities of violinist. There are violinists who practice for hours to be in shape, but there was no need of doing that for Oleg. I was always amazed at how easily he played, how quickly he could learn, how broad his repertoire was. Under lightness I, of course, do not mean superficiality but the Mozartian lightness which stems from character, certain qualities of personality. Alas, he was very young when he passed away! He died too young to acquire something that makes a person seasoned, weighty figure; therefore his lightness was perceived as organic trait of a young soul. We will never know what heights would he have achieved in his comprehension of music.

Whether contemporary musicians listen to records of Oleg Kagan or not, I do not know; the life is so crazy with its pulse racing faster than it did before. Whirlwind of developments push young people to speed up in order to do as many things as possible. Of course they know much and listen to everything. Those who have listened to him admire him. However, the present market of records is inundated with anything whatever exists; everything can be downloaded from the Internet. Therefore, the act of listening has stopped to be an event, a shock. They listen while moving – in a metro, on a train or a plane, and not for receiving pleasure but rather to be aware of developments.

There is a record, available on the Internet, of Beethoven’s triple concerto performed by you, Arnold Kats, Natalia Gutman and Oleg Kagan. What do you remember that concert for?

I did not even know that that record of concert was kept in the archives. Judging by my emotional state, feelings which I experienced then, it was an important and very successful performance for me. We all were somewhat elated. Kats conducted that concert amazingly – he actually led it. I have always had a very good creative relationship with Kats. In short, that was a memorable event for me, especially considering that it was almost my first performance of triple concerto.

Do you remember you performing all concertos of Beethoven with the orchestra of Nizhny Novgorod at a festival held in memory of Oleg Kagan in Kreuth?

Of course I do. Unfortunately, the festival has now transformed into something different from what it initially was. But there is a chamber music festival in memory of Oleg Kagan in Moscow, while in October we dedicate our festival in Telavi to 70th anniversary of Oleg Kagan. Negotiations are now being finalized regarding participants and program of the festival.

His teacher at the Riga Music School, Joachim Braun, described Kagan as “subtle and refined child” and believed that these very qualities ensured his success. We once had a wonderful epoch when a refined nature could ensure success of a musician. Are we dealing with an inborn trait here or is this something that may be developed by a person? We have a period of capital formation now, the epoch of parvenu and speaking about refined nature of a person has actually become tantamount to bad manners, a sort of arrogance though for many it was the aim of self-perfection in the Soviet times. In your interviews you repeatedly say that there are many perfect performers when it comes to prowess today, but few personalities and you recall the past when, in your opinion, the things were different. Apparently, Oleg Kagan is the figure from the past whom you mean when talking about this issue. Does the notion of “personality” amount to the notion of “refined person”? Is this what a person and a musician must strive to achieve?

When I start ruminating on what you have just asked, I often find that I am lost. I admit that this is a serious topic and I find it increasingly difficult to articulate my feelings. It is not very clear to me what a “refined personality” means today. As regards Oleg Kagan, it would be much easier for me to speak about him had he lived as long as I have. It is extremely difficult to talk about someone whose life was too short to allow him/her to fully express himself/herself.

When I listened to Oleg’s live concerts I could spot vast resources in his each performance, vast possibilities for other interpretations of the same composition. For me this is the proof of personal talent rather than musical talent. I believe that only a person with rich inner world may possess such resources which then materialize in his/her performance. And it breaks my heart that his death left these resources unused and a huge amount of interpretations did not occur. His play suggested innumerable possible subtexts, details, nuances which could have become available to public. Other performers do not see or hear those nuances. There is a performance which seem to be carved in marble and it is perfect in its own way, but at the same time the performer is not able to discover anything else in the composition. In case of Oleg Kagan, however, that same marble sparkled with new hues each time; he searched for new images in it and each time, made a listener believe in its power and beauty. What I’ve just said reminded me of Kagan’s performance of sonata №5 by Beethoven. Oleg discerned so much in it and could have discovered a lot more had he lived longer!

The same holds true for Rondo Capriccioso, this much-performed violin hit, which he played so that each time he performed it you had a feeling that you were listening to an entirely new composition. However, when listening to contemporary pianists or violinists, I do not have this feeling of limitless possibilities of a personality to interpret a composition, although some of them are often described as “great” or “outstanding.” I think, it is clear that today, tomorrow or thereafter they will continue playing in the same manner, like much played vinyl records or a computer with one and the same function. I am saying this with regard to manifestation of personality in performance.

As for “refined nature,” I think it manifests in the absence of desire to necessarily impose oneself, one’s opinions and views on others. A refined person always gives you freedom, is tolerant to many things without hostility and judgment. Such a person will not point to your flaws, will not emphasize what he/she dislikes in you. In music, refinement is an elusive notion but if it exists it is a strength, not a weakness. For me the refinement of a person is in how he/she steps onto a stage, how he/she approaches the instrument, how he/she sits at it or holds a violin or how a conductor treats musicians of orchestra. These are rather additional qualities to musical qualities. Dear me, I am not used to speaking about refinement of other people. I am speaking and thinking – is this really me or not?

All right. What, in your opinion, contributes to developing a personality? Books?

No.

Music? It seems many musicians play same compositions but all of them significantly differ from one another by their views and actions. Perhaps, a personality is not formed thanks to art but as a result of suffering and deprivation as religions teach? Or owing to genes?

Yes, one cannot do without genes here. But besides genes an important thing here is also the attitude towards yourself: what do you expect from yourself? Who do you like to be? What are your priorities? What are your values? For instance, from an ordinary person’s viewpoint I live in a bad residential house in Moscow and I am often given advice what to do in order to change the apartment. But when I imagine what I have to do to change the apartment, how much of my time should I spend, which I need to achieve my inner goals and do things that are way more important for me than changing the apartment, I do not even want to think about that. Every person, including a musician, has a choice. I do not say that living in a bad apartment and being poor is good. I will never say that. But an answer to a question what do you prefer, what do you primarily intend to spend your life and time on, will speak much about a personality. For example, I am obsessed with teaching, it is important for me to spend time on youth, teach them, open up something for them. I myself make discoveries together with them to date. The same held true for Oleg. He was an excellent teacher! Had he been alive he would have raised famous musicians because he had the gift of teaching too and considered teaching a serious occupation. Thus, a personality is an individual who makes a choice in favor of certain important ideas, when you cannot step over something inside yourself and no one and nothing will force you to do that. However, many will say that this is nonsense. I am also often told this. But this is my inner belief and I will die with this belief unaltered. In this sense we all – I, Natasha Gutman, Oleg Kagan and Richter were identical: they adhered to the same principles, it was natural for them and could not have been otherwise. Whether it is possible to learn this, I do not know.

What would you like to say about Oleg Kagan yourself, without my questions?

Well, I thought before this interview what I would tell you. But I find it difficult to speak about him. It would be much easier to say something about other people. Oleg was with us not for a long time and died so young that for me he is not over yet. I can speak about him only with pain. On the one hand, he established himself as an artist and a master. On the other hand his path halted abruptly at the edge of the abyss and I do not know what is there, beyond that edge, on the bottom of that abyss – it is darkness for me there.

Well, I thought before this interview what I would tell you. But I find it difficult to speak about him. It would be much easier to say something about other people. Oleg was with us not for a long time and died so young that for me he is not over yet. I can speak about him only with pain. On the one hand, he established himself as an artist and a master. On the other hand his path halted abruptly at the edge of the abyss and I do not know what is there, beyond that edge, on the bottom of that abyss – it is darkness for me there.

Success in our profession depends on many details – the attention of managers, a great number of concerts, wide popularity among public… It would be fair for Oleg to have all these. The absence of wide popularity frustrates some people and there are many examples of this. It might be unpleasant to be told that someone has toured the world, has played with orchestras of Vienna, Berlin and New York. But Oleg knew his price perfectly well, understood his worth. He knew that perhaps even better than people close to him.

We were glad to perform in our country. I judge by myself, of course, and I was happy that I had my audience in Moscow, Leningrad, other cities where I was admired and waited for. Oleg and Natasha felt the same. That was important for us and we did not feel being deprived of our due share. As for foreign countries, I performed in absolutely unknown towns somewhere in Hungary, Poland, but never suffered from that. It was not pleasant, though. Sometimes I was told about someone having travelled to Paris as often as I travelled to Kutaisi. Therefore, Kutaisi was the most western city for me over a certain period of time. That was the lot of many artists of those times. Moreover, in those years, various desk officers of Gosconcert, who were busy moving papers from one desk to another and were not able to appreciate either music or musicians, “categorized” us according to which country we were planning to go and treated us accordingly. If you were planning to travel to a capitalist country you were considered a first-rate person whereas if you were travelling to Eastern Europe you were not a person at all (laughs). Thank god we were able to understand, without any help from Gosconcert, who we were: we had friends and dedicated audiences. My first concert in the West took place in 1974, when Géza Anda fell ill and I was asked to replace him. Our relatives and close friends were more distressed about that than we ourselves. The same holds true for Oleg. His friends were concerned but he often stayed calm. Many artists left for and stayed in the West. But Oleg did not even think about that. However, had he immigrated, I think, he would have made a brilliant career there.

But everything happened as it was destined by fate.

His fabulous talent was not fully appreciated by everyone and he did not receive that degree of popularity he deserved. It is a pity. His last concert in his life – the one he played several days before his death, is impossible to listen to without tears even today; and not only because you know that he would soon pass away, but also because even in that end-of-life performance, regardless of his disease and weakness, he still showed his radiance, depth of his obsession with something very important inside him, i.e. his main musical and human qualities.

Was he a happy man?

Absolutely! He enjoyed life and everything he had. He never dwelled on troubles. He had perfect family,

wonderful children, excellent friends. He was absolutely happy.

www.belcanto.ru

Translated by K. Mskhiladze