On the 100th Anniversary of Sv iatoslav Richter

Olga Yusova

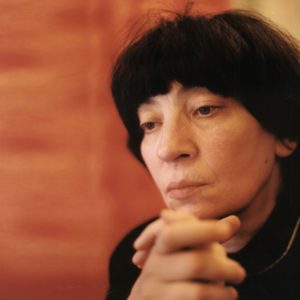

INTERVIEW WITH ELISO VIRSALADZE

Eliso Virsaladze has inaugurated a series of concerts dedicated to the 100th anniversary of Sviatoslav Richter, which is held in Nizhny Novgorod Concert Hall. Performers in the concerts include Natalia Gutman and this seems quite natural as both these artists belong to the community of musicians known as Richter’s circle. Both of them were connected with Richter by long-term friendship, intensive intellectual relationship, creative cooperation, joint performances, experiences of happy or unhappy events.

Eliso Virsaladze has inaugurated a series of concerts dedicated to the 100th anniversary of Sviatoslav Richter, which is held in Nizhny Novgorod Concert Hall. Performers in the concerts include Natalia Gutman and this seems quite natural as both these artists belong to the community of musicians known as Richter’s circle. Both of them were connected with Richter by long-term friendship, intensive intellectual relationship, creative cooperation, joint performances, experiences of happy or unhappy events.

The first evening of the concert series saw the performance of three piano concertos – those of Edvard Grieg, Franz Liszt’s first piano concerto and Maurice Ravel’s second piano concerto (for the left hand). The pianist performed with the academic symphony orchestra of Nizhny Novgorod Concert Hall, conducted by Aleksandr Skulsky. The

audience of Nizhny Novgorod will also see the joint performance of chamber music by Eliso Virsaladze and the violoncellist Natalia Gutman as well as a solo concert of the latter. In her interview given to Belcanto.ru on the eve of the concert, Eliso Virsaladze recalled her relationship with one of the greatest pianist of the 20th century.

Ms. Virsaladze, do you remember when you got acquainted with Sviatoslav Richter? Did you attend concerts which he performed in Tbilisi? I have read that Heinrich Neuhaus often spent his holidays in Tbilisi and Richter used to visit him there. Were you aware of that?

– The first time I listened to Richer was at a concert held in Kislovodsk; I was nine years old then. I have a vague recollection of that concert, but I definitely remember it. Although I was a child the name of Richter was already very important to me. He visited Tbilisi from the very start of his career, staying at his friends’ places for quite long periods, practicing, building his repertoire and even performing during the war as well as thereafter. I did not maintain chronological records of his performances, but, I think, he visited Georgia almost every year. True, Neuhaus often spent his holidays in Georgia, staying in mountains, and Richter travelled there to see him.

One of his travels to Tbilisi had a tragic reason – a very famous pianist, professor of Tbilisi Conservatory, Valentina Kuftina, killed herself after the tragic death of her husband who was a scientist archeologist. Richter dedicated his concert, held shortly after Kuftina’s death in Tbilisi, to her. They were great friendsand he respected her as a musician and pedagogue. I attended that concert.

In my conversations with my grandmother in our family, we often talked about Heinrich Neuhaus as my grandma knew him and they often interactedas teachers. However, she was not able to discuss Richter’s performances with me because at the time when I started attending them, my grandmother was not able to leave the house and therefore, could not attend his concerts.

In 1962, in Moscow, you were practicing for the 2nd International Tchaikovsky Competition and it was Neuhaus who took care of your practice. Was it during that time that you met Richter? Did he notice you exactly at that time?

– I think, he did not notice me at all back then and I am not sure whether he arrived at that event because he had quite an unpleasant experience of the 1st competition which he attended as a jury member for the first and last time. Therefore, he stayed away from the second competition. But his wife, Nina, listened to my performance in the first tour of the competition; I remember that very well. However, in that very year I went to his apartment. This happened because Heinrich Neuhaus did not have a flat at that time and he and his wife lived in Richter’s apartment. Thus, it was for the first time in my life that I found myself in that apartment and in that famous atmosphere.

So, first Richter, in his youth, lived at Neuhaus’s place and then, vice versa.

– Absolutely right. Richter made his flat available to his teacher. But I did not meet Richter then; I went there to practice under Neuhaus’s instruction. It was not until 1966 that we got acquainted. That was the only occasion when he provided me with a lesson in his apartment. I played Mozart’s piano sonata in B-flat major, K. 333 to him. It was that very sonata that I startedmy recent performance with in commemoration of Richter at the festival December Evenings.

– Absolutely right. Richter made his flat available to his teacher. But I did not meet Richter then; I went there to practice under Neuhaus’s instruction. It was not until 1966 that we got acquainted. That was the only occasion when he provided me with a lesson in his apartment. I played Mozart’s piano sonata in B-flat major, K. 333 to him. It was that very sonata that I startedmy recent performance with in commemoration of Richter at the festival December Evenings.

Back then, however, I deliberately selected a short piece of work for the lesson during which he told me such things that I will, of course, never forget. He shared his associations with me regarding various episodes of the sonata. I remember, in the second part of sonata, he made me draw my attention to one harmonic passagein which he saw a harbinger of Wagner.

One of books about Richter quotes his words about Mozart. Richter says he feels shortage of “freshness” in Mozart. Richer blames Mozart’s father for that who, in Richter’s opinion, excessively exploited the talent of his wunderkind child.

– I do not trust books about Richter much. This might have been said by him when being in a certain mood. True, his opinions on many issues were unfaltering, but this does not hold true for all his statements about life and music. Some of his views were not hundred-percent convictions at all. This is especially true about Mozart.

I had frequently heard opposite opinions of Richter about Mozart, let alone the fact that he performed his works quite often and the way he performed them totally refutes the quote you cited above.

In general, he was a person of moods. Therefore, when I am told that he wrote about me such brilliant words, I do not allow myself to be overwhelmed by euphoria over them. Yes, he wrote nice words about me in his dairy and I do no argue that it is, of course, pleasant when a person of such magnitude as Richter said something nice about me! However, those words should not be exaggerated but treated with some restraint.

I believe that owing to that expression, many perceive you as a musician of his circle. Did such a notion as “Richter’s circle” exist? If it did, was that circle, in your opinion, narrow or sufficiently wide?

– Some musicians knew him for much longer period of time than I did and they had closer relationship, for example, Natalia Gutman. As regards me, I may say that I was privileged to be his acquaintance during a certain period of time in my life.

Even those recollections which you think are insignificant are very valuable for us today.

– I understand that because there are so many myths invented about Richter as well as rumors circulating which are wide of the mark. At the same time, recollections about him are difficult because he was so multifaceted and diverse that no recollection will be absolutely accurate. Similarly, everything which he pronounced, all his words cannot be perceived as dogma. Moreover, he is the personality of such a gigantic scale that one is required to narrate about him in a superlative degree.

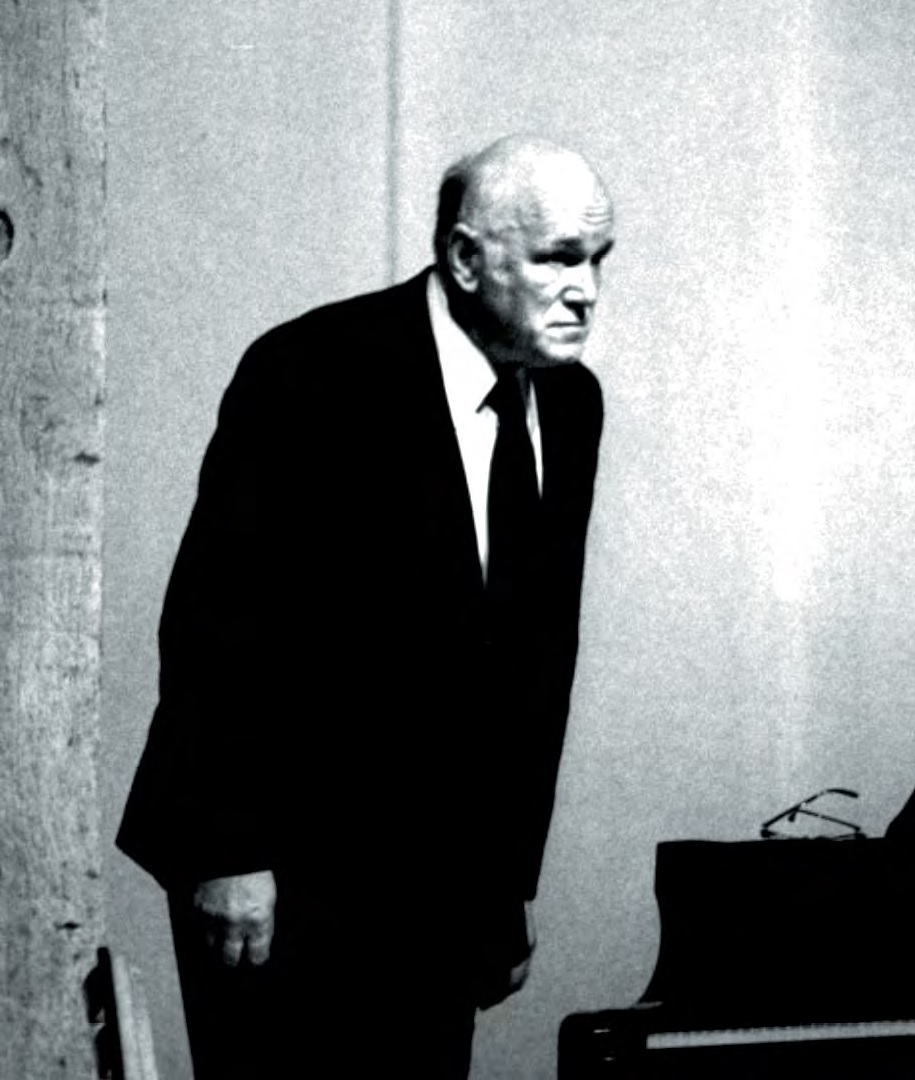

What I want to say is that the superlative degree is exactly the mode to recollect him. He was indeed such a phenomenon – an outstanding, unique person, endowed with talents in various areas. He could have become a painter, an actor, a stage director or a conductor as well as, perhaps, a composer, if he wished so.

But he became a performer and remained loyal to his choice to the end of his life. This is already a unique instance. I know quite a number of musicians who “dumped” their musical instruments to take up a new task of directing orchestras. They, of course, cannot be called professional conductors. Even the fabulous Mstislav Rostropovich was not a conductor of highly professional scale but rather a great person who, standing in front of orchestra, inspired people with his charisma.

Richter was also capable of becoming such a great personality.

– Naturally. That’s what I am talking about. But Richter did not become such. I do not know what made him to stay focused on his musical instrument alone. Unfortunately, I never heard any explanation of this from Richter. The explanation should probably be sought in the fact that a piano holds in itself innumerable possibilities for a performer. No life is sufficient to open up al its treasures – this is what I tirelessly reiterate.

It is a well-known fact that Sviatoslav Richter was keen on finding parallels between musical images and literary or artistic images. Is such a musical reasoning familiar to you? Does music give rise to such concrete associations with other works of artin you? I know that many performers consider the language of music as an abstract one and hence, various associations give content to certain works of music, which an author of musical piece did not have in mind.

– Let me admit that when it concerns me the things are quite different. Images which arise in me seem to exist and not exist at the same time. They cannot be called realistic; often they have no analogues either in life or in other forms of art. They are not concrete but rather absolutely abstract. They are so very individual that I often cannot share them with others. When I work with students I am merely able to point out something concrete only in general terms, for example, the idea about a physical state of a person – that is, sometimes the music itself hints about tiredness or, on the contrary, uplift, sorrow or gaiety. All this emanates from the nature of music itself and is always associated with that particular composition and has nothing to do with the image of another artwork.

How can you explain the entirety of those conditions which makes it possible for such a genius to emerge?

– Richter is a unique phenomenon. All his properties were congenital. No matter whereand when were he born he would have been of the like he was and we knew. It is hardly possible to list all those characteristics that give such a unique amalgamation, such an incredible result. His natural capabilities were multiplied by fanaticism and love to art. He was equally fond of many fields of art. I was always amazed about him knowing everything and remembering everything. At the same time this was not a mechanical remembering but rather the experiencing of each fact of art through. Everything which he read, saw or heard passed through his heart. No small things existed for him; he used to attach meaning to everything, get to the heart of all developments, feel through everything, never ignoring details of life.

– Richter is a unique phenomenon. All his properties were congenital. No matter whereand when were he born he would have been of the like he was and we knew. It is hardly possible to list all those characteristics that give such a unique amalgamation, such an incredible result. His natural capabilities were multiplied by fanaticism and love to art. He was equally fond of many fields of art. I was always amazed about him knowing everything and remembering everything. At the same time this was not a mechanical remembering but rather the experiencing of each fact of art through. Everything which he read, saw or heard passed through his heart. No small things existed for him; he used to attach meaning to everything, get to the heart of all developments, feel through everything, never ignoring details of life.

You must agree that his famous tours of Russian cities were the manifestation of admiration toward human beings, absence of arrogance, and I think that many musicians of various generation, including even young ones, try to imitate him in that.

– Indeed. The most amazing is that he did that absolutely natural, without any play-acting and desire to show off his generosity. He merely wanted to perform in such locations where no one had performed before. It did not matter in what concert hall or even on what grand piano he would perform; he was not demanding in this regard. As far as I know, he was always accompanied by a piano tuner. As you understand, however, this was not always sufficient to improve the quality of the instrument. Learning about a pianist travelling for a concert to a city or a country with his/her piano always raises a laugh in me.

From numerous recollections about Richet one may conclude that he was absolutely indifferent to everything material.

– He was indeed so indifferent that did not even know how much things cost in a shop. He did not know the value of money. That was an organic trait of his personality and his love for art looked quite natural against this lack of interest towards the material world.

He named Wanderer Fantasy by Franz Schubert as his favorite piece. Do you associate with him the image of a wanderer, genius, a person indifferent to rough material world, with aspiring feelings and thoughts?

– We are all wanderers in this life… He, of course, was not a stranger to philosophy. Perhaps it is exactly how he explained his love to that piece of work. Uh, one can recount so much about this person and draw so many different parallels… First and foremost he was a great artist. Just like his performances were not unfaltering, one cannot take someone’s opinion about him and even his own opinion about himself as something unfaltering.

His every performance was absolutely different from his previous ones. For me this is the most valuable trait in an artist. Richter was extremely diverse. A performer who always performs in the same manner is not an artist. An instantaneous birth of a musical piece occurs on the stage and as the concert ends that piece of music becomes a thing of the past too. That’s an instance that ends and no longer exists. Theatre can only be partially compared to musical performance; there is, of course, a possibility of variation in performance. But theatre has words, many actors and also a stage director who influences the play of actors. When performing

music, however, you are the director yourself.

Was Richter disappointed about the reaction of audience? In provinces the reaction of audience was not always adequate; listeners were not always able to adequately appreciate the uniqueness of every interpretation by Richter. Did he play for people or just for creating a perfect variant of performance?

– His objective was not to lower himself to the level of audience but vice versa, to elevate it to his level. Listening to his performance was not fun, not always bringing pleasure, but, in the first place, it was a difficult mental work. Listening to Richter was not an easy task.

Valentina Chemberdzhi describes one of his performances in the Grand Hall of Conservatory: Richter played The Symphonic Etudes by Schuman in the first part of the concert and even more so, played so brilliantly that he himself was content with his performance, but he received only moderate handclaps. In the second part of that concert, however, his performance of Pictures at an Exhibition was, in his opinion, unsuccessful, although the audience burst into wild applause. He felt offended by such an inadequate reaction of listeners.

– Such things often happen at concerts, this is normal. You think that you are playing well but people do not like it and vice versa. All this is a very subjective matter. Sometimes it is absolutely impossible to explain why your energy fails to capture the audience. Numerous various nuances may affect the process of exchange of emotions with the audience. There are occasions when a concert turns for a performer into a fight with own self in order to move up to a needed condition and reach the people in the concert hall. Everything is unpredictable.

Does counting up to 30, as Richter taught, help?

– He had everything pre-staged in his performance. He used to say that when he played Liszt’s Sonata in B minor, counting up to 30 helped him to achieve the absolute silence in the hall. Of course, the ability to concentrate is necessary but this does not mean at all that one should precisely imitate him in that. Sometimes you can see a young performer coming out on the stage and it is obvious that he is sitting at the piano and countingsilently. This seems a bit ridiculous.

What was the reason of Richter’s strong dissatisfaction with himself? “I do not like myself” – the famous final words pronounced by Richter in Bruno Monsaingeon’s documentary is painful to hear.

– I think that at the moment when this phrase was pronounced he was overcoming a difficult physical state and when a person endowed with such love to life, power and energy is very sick, it is completely understandable that he is dissatisfied with himself. As regards the performance, discontent with and high demands posed to oneself are something very natural because such a musician always aspires towards performing that perfect variant which he hears inside himself. Sometimes, Richter spent hours and days to find it in a small phrase or in several bars. I like Artur Schnabel’s words: “I want to play only music which is better than it could be performed”.

This is something that, perhaps, may be said about many pieces of music.

– In fact, about the entire repertoire of a pianist. No matter how much we play, it is impossible to be content with a performed music.

What I partially meant in my question is that whether you discerned in him the hidden sorrow which is characteristic for many great personalities and is often described by many of them as “bitterness of existence.”

– Yes, absolutely, this is how it was. It could not have been otherwise. This is natural.

– Yes, absolutely, this is how it was. It could not have been otherwise. This is natural.

In her book Chemberdzhi wrote that after an excellent concert he felt devastated and said: “Why is it that when everything is fine you still feel sorrow and remorse?”

Thank god this was not his only state of mind. I am afraid that that quote might build a distorted impressions about his character among readers. It is absolutely possible that he said those words under the impact of a moment, as a result of tiredness. I want to say that such notes, such recollections are a very fragile thing; they may mislead because they do not encompass the entire diversity of expressions of Richter’s personality.

Vera Gornostayeva noted that in the presence of Richter it was impossible to say something negative about any other person. Do you agree with that?

– Indeed. He never spoke ill about anyone; at least, I have never heard anything like that from him. This, however, did not mean that there were tabooed topics. One could speak with him about many things as he was an absolutely natural person. I, at least, never feared to say something to him and hear his reproof, condemnation. In the presence of such a person a sort of inner control,of course, becomes activated and this is absolutely normal. Moreover, there were no aggressive people in his circle and topics of talks predominantly concerned interesting and elevated things.

Could it be said that kinship between you two was also influenced by tragic fate of close people – Richter’s father was executed as well as your uncle.

– I never talked with him about this topic and I am not sure whether he knew about the tragedy of my family.

The point is that such families were many at those times; in our milieu almost everyone had either one of their parents or relatives executed or arrested. However, I cannot rule out that his friends in Tbilisi told him about my family when he visited Tbilisi.

One must speak in broader terms: the kinship you mentioned extended to many people. That was a fact of our life and there is no escaping that fact. It is terrible that the kinship was based on such a tragic ground. It is also terrible that people in such circumstances faced the objective to survive. You had to live, you had to choose a path to life. And that path was not always straight and honest. People tried to survive in various ways. Some got adjusted to new realities, becoming a member of communist party, not seeing anything shameful in making such a compromise. Others, in order to continue with their work in their profession, signed some letters thus saving their skins and getting a chance to perform, to create. But there was a third category of people who rejected any compromise with the conscience and therefore, their path proved way more difficult.

It is a well-known fact that you performed at the very last concert in Richter’s life, which he, being very

ill, attended on 22 June 1997.

– Correct. Natasha Gutman, Viktor Tretiakov and I performed Trio by Shostakovich while I performed The Grand

Piano Sonata by Tchaikovsky in the first part of the concert. Frankly speaking I did not even know that Richter would come to that concert because he already felt very weak. That was his last living festival in Tours, France.

Vera Gornostayeva named you among those few people in the presence of whom Sviatoslav Richter passed away, and she said that it was owing to such people that he was happy in the final days of his life.

– I cannot claim that. I indeed visited him in his apartment in Nikolina Gora three or four days before his death. It was very difficult, merely unbearable to see how he was fading away; even now I shun recalling those days. There are several very dreadful recollections in my life which I try to shun andone of them is the recollection of how Richter was passing away. After so many years from his death I still find it difficult to speak about that.

You mentioned about the festival of Richter in Tours. However, you are among those few musicians who participated in almost every December Evenings. Can you recall how this festival started?

– It was Richter who personally invited me to that festival and until he was alive I participated in the festival many time, though thereafter, rarely. December Evenings was entirely his idea – an absolutely innovative, even revolutionary idea. There are many museums in the world which are used as venues for musical evenings, but this festival was extraordinary in a certain way. Richter combined painting and musicin it; he himself made decisions on the theme of each festival and the content of the program and it was always exquisite, elitist in the best meaning of these words. Very many musicians arrived to this festival not merely for performing in Moscow, but especially to him and only because he invited them; they were honored by that invitation and spelled by the idea of the festival. The respect towards him was so great that an idea that one may turn down his invitation because of a busy schedule ever came to anyone’s mind.

To conduct December Evenings was not an easy task, but owing to Irina Antonova who became an associate and fellow thinker of Richter, everything was perfectly organized. Merely, the museum itself is a bit uncomfortable venue for performers as some purely technical details are not envisaged there; for example, there is no place for performers to warm up before a concert. But all these small inconveniences were nothing compared to the happiness about being a performer in the festival organized by Richter. Moreover, the festival was unique – the presence of such a gigantic person added a huge significance to the Evenings.

May your own festival in Telavi be named an event of Richter type as there is always a strong educational emphasis in all festivals?

– When in 1980s we, together with Oleg Kagan and Natasha Gutman, began to conduct it, we wanted to dedicate it to Neuhaus. But that idea did not realize. Had we organized it in Tbilisi, it would perhaps have been easier. But since the festival was conducted in Telavi, we were to take into account local peculiarities.

Dedication of an event to Neuhaus would be artificial whereas I did not want it to look artificial. It was not until the recent years that the interest towards the festival notably increased. Therefore, the next festival which is slated for October will be dedicated to Richter. Moreover, the manor of prince Chavchavadze, whose daughter was married to Alexander Griboyedov, will be used as a venue for an exhibition of painters who were close to Richter and paintings of Richter himself will also be exhibited there. Listeners arrive to our festival from all over Georgia; teachers bring their students since master classes are held in parallel. Young musicians also participate in concerts, for example, David Oistrakh Quartet comprising very talented musicians; I have already performed with them. A festival orchestra specifically gathers together each time.

Ms. Virsaladze, what would you like to recount about Richter yourself? What are those recollections that you would like to share with in regards with his anniversary?

– We always try to give a shape to our feelings, thoughts, recollections; to fix something, freeze some beautiful moments. This is almost impossible. I fear I will say something and it will turn out a lie. Even the tone of interjections is important when recollecting such a person. You must have noticed one characteristic feature of many recollections: everyone suddenly turn out to be very close friends of a dead genius. This is ridiculous. Moreover people mix their own fantasies, guesses with recollections. Take a couple of books and you will see that every author depicts his/her own Richter. You will not be able to reconstruct one image of Richter, even having read all the books written about him.

– We always try to give a shape to our feelings, thoughts, recollections; to fix something, freeze some beautiful moments. This is almost impossible. I fear I will say something and it will turn out a lie. Even the tone of interjections is important when recollecting such a person. You must have noticed one characteristic feature of many recollections: everyone suddenly turn out to be very close friends of a dead genius. This is ridiculous. Moreover people mix their own fantasies, guesses with recollections. Take a couple of books and you will see that every author depicts his/her own Richter. You will not be able to reconstruct one image of Richter, even having read all the books written about him.

I do not hundred-percent trust some of my own recollections. For example, I cannot recall several details of his performance though when being in Moscow always tried to attend all his concerts. Each time it was a monumental, outstanding event. I remember how he played all preludes and fugues of Bach – first volume, second volume – at Merzlyakov college of music. One can hardly describe what was happening there! It was impossible to get there and that despite the fact that there were no announcements made about the performance, no advance notification sent to anyone. An enormous crowd of people was unable to get there. One can remember his concerts in the Central House of Art Workers as well as other performances. I do not want to hurt any of great performers – be they national or international, but some concerts of Richter were taking your breath away, after them it was impossible to come to one’s senses. It was difficult to compare anyone with him. His performance seemed to be carrying you away somewhere and you remember this very state of yours throughout your life. I might fail to reconstruct some technical nuances of his performance but I will never forget the incredible impression I received and the unearthly state I found myself in from those concerts.

Does any of current performers make such a strong impression on you?

– Unfortunately, very rarely. I can sometimes say that I liked something very much; I can also get excited about someone’s performance, of course. But I cannot say that I was struck dumb from someone’s play.

I think there are many factors in the modern world that steal away spiritual energy from people, forcing them to waste it on unworthy things. That is why the art of performance fails to reach the heights of Richter and listeners are unable to experience ecstasy from performance.

– Yes, this is true. You might be excited about the technical prowess, virtuosity of a performer but when such a performance ends it leaves nothing in your heart. This is fearsome. We all – performers and listeners – have degraded to a lower scale.

Yet another moment. You might find it amusing, but it seems serious to me. I noticed that looking at any of greatpersons you see that they treat nature, animals with reverence. Richter was no exception, of course. Seeing a cat sleeping on a chair, he would never shoo it away from the chair, but keep standing in order not to disturb the cat.

– This is correct. But that was not a sentimental tenderness, but a serious philosophy of life. I do not think that if a person does not like animals he/she does not like people either. But when I learn about ruthlessness of a prominent person towards animals, I start to treat him/her differently. In general, I am astounded at what the mankind does instead of joining forces and responding to challenges they face – to save nature and themselves. All passions of a human being is, in fact, so insignificant compared to the importance to protect the nature which is merely necessary for our survival. We all have only one life! When you think of what those people who go to wars, kill people and animals, spend it, it overwhelms you with fear! At the same time, we know how geniuses like Richter lived through their only life. Although the time they lived in was severe and losses were heavy, they nevertheless were able to use their energy to transform the life around them according to a pattern they represented themselves.

What about your students, are they interested in Richter? Do they ask you about him?

– Students differ from one another. Some students have a perfect knowledge of the history of pianism in our country, including the facts from the biography of Richter. There are such students who are less interested in that. You may sometimes meet musicians who, though having modest abilities, treat themselves too seriously. Today, everyone consider themselves geniuses, stars and even more so, by birth. I have even heard disparaging statements about Richter. You know, this is just ridiculous.

When Richter was alive, the mere fact of his existence restrained the community of musicians as well as all those who knew and valued him, from doing something bad, base, obscene. Personalities of such a scale raise the standard of acts and deeds, point out the path towards truth, illuminate their environment. Anyone who comes to fall within their orbit, starts to move up to that standard, tries to comply with it, to improve him/herself and sometimes surpasses the capabilities assigned to him/her by the nature.

Fortunately, his memory does not allow us even today to make a mistake and confuse the imaginary greatness with the genuine one.

Translated by KETEVAN MSKHILADZE